The Mellwood Distillery Company and General Distillers History

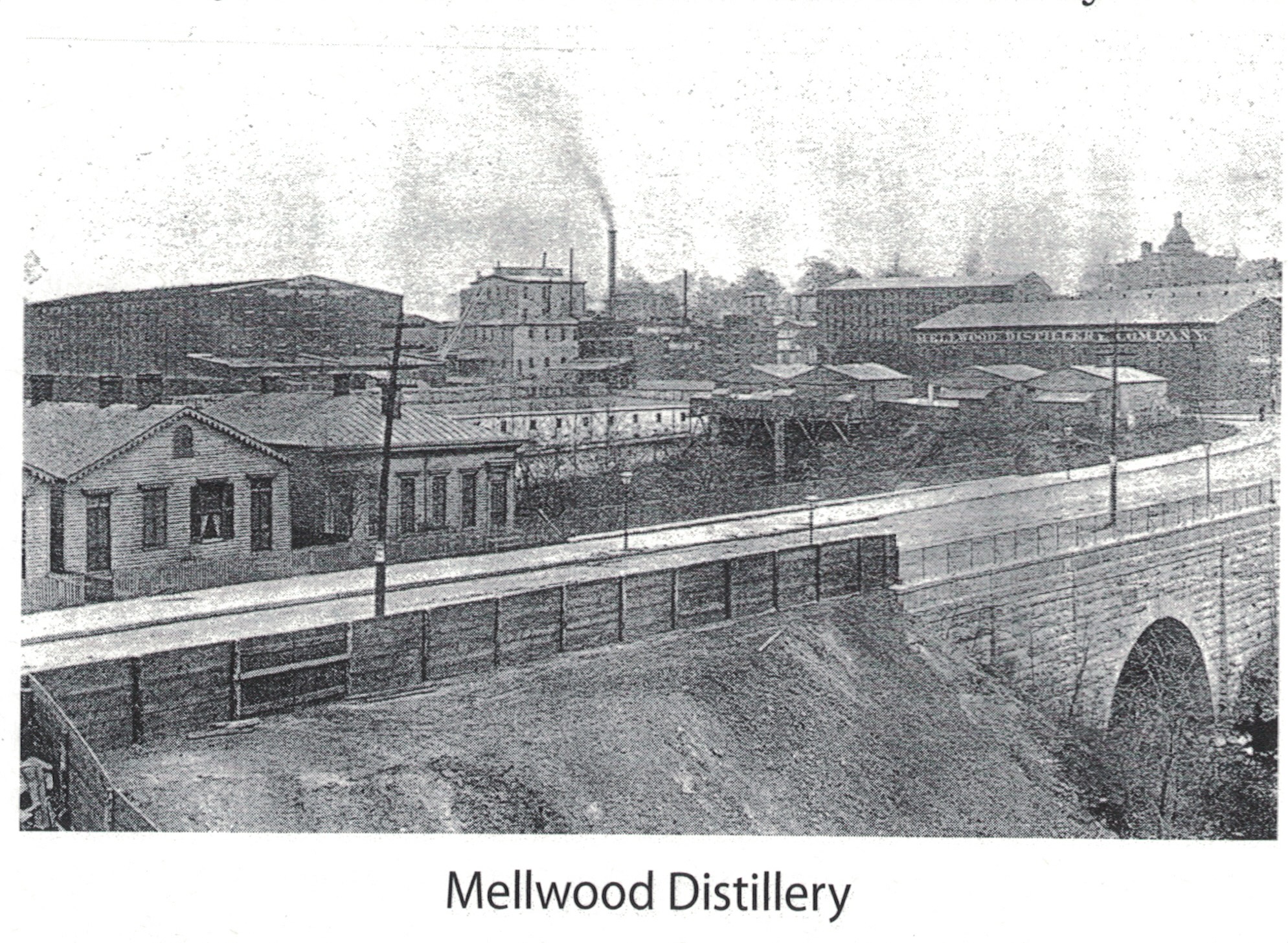

The story of Mellwood Distillery, nestled on the banks of the South Fork of Beargrass Creek in Louisville, Kentucky, just after the Civil War, is a fascinating journey of entrepreneurial spirit, accidental branding, legal battles against deceit, and eventual adaptation through tumultuous times like Prohibition.

FROM MILLWOOD TO MELLWOOD

Our story begins with George W. Swearingen, born in Bullitt County, Kentucky, in 1837. Descended from a Dutch settler in Maryland, Swearingen came from a family with deep roots in America and Kentucky. After graduating from Centre College, he initially pursued farming but, like many in the post-Civil War South, sought new opportunities.

Our story begins with George W. Swearingen, born in Bullitt County, Kentucky, in 1837. Descended from a Dutch settler in Maryland, Swearingen came from a family with deep roots in America and Kentucky. After graduating from Centre College, he initially pursued farming but, like many in the post-Civil War South, sought new opportunities.

In the latter part of the 1860s, Swearingen moved his family to Louisville and embarked on a new venture: distilling whiskey. Shortly after the Civil War, in 1865, the firm of Swearingen & Biggs, with Mr. George W. Swearingen of Bullitt County being the senior partner, built the Mellwood Distillery. It was located on the north side of Mellwood Avenue (Reservoir Ave.), between Frankfort Avenue and Litterle (Bardstown Road) on Bear Grass Creek. Mr. Swearingen was president and principal owner.

Swearingen intended to name his distillery “Millwood” after his small still on his family farm. However, when ordering his brand, the name was reportedly misspelled as “Mellwood,” a serendipitous error that Swearingen decided to embrace. This name eventually became so significant that in 1895, Reservoir Avenue was renamed Mellwood Avenue in its honor. Mellwood Distillery Co was designated Registered Distillery #34 (RD#34), 5th District of Kentucky.

From 1867 to 1874, the distillery was operated by Biggs, Patterson & Company, which was comprised of Andrew Biggs, William Patterson, and G. W. Swearingen. In 1878, the distillery was owned and operated by Swearingen & Biggs, G. W. Swearingen, president, and Andrew Biggs, secretary and treasurer. By 1880, Mr. Swearingen was still listed in the Louisville directory as president; however, Mr. Biggs was no longer listed as secretary, treasurer.

By 1884, Mr. Swearingen was listed as president of both the Mellwood Distillery, and the Spring Water Distillery, RD # 4, located near Bowling Green, Kentucky. By 1889, Mr. Biggs was listed as the owner of the Old Times Distillery, RD # 297.

From a modest start, Mellwood Distillery grew rapidly under Swearingen’s leadership, becoming one of the largest and most successful distilleries in Kentucky. The plant expanded to occupy twelve acres, boasting five immense bonded warehouses and one “free” warehouse. The distillery had an equipped mill room with a series of patent roller mills. It also had a large fermenting house that contained nineteen vats or tanks, with each having a capacity of ten thousand gallons, besides the vast beer well in the center. The plant also had a boiler room, barrel rooms, a branding house and large cattle feeding pens with accommodations for one thousand head of cattle. For four months of the year, the distillery would shut down. One of its warehouses could hold 36,000 barrels of bourbon.

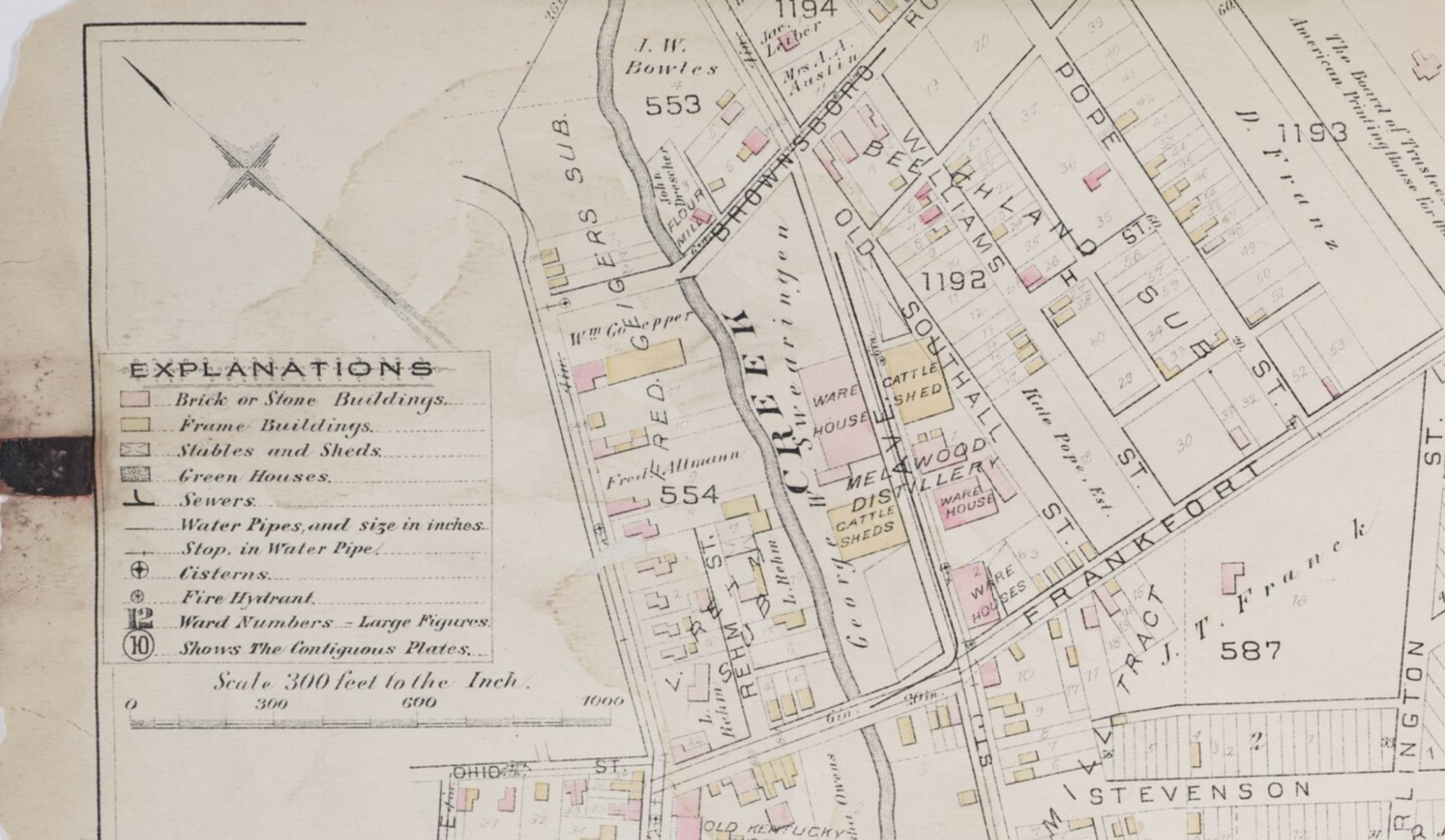

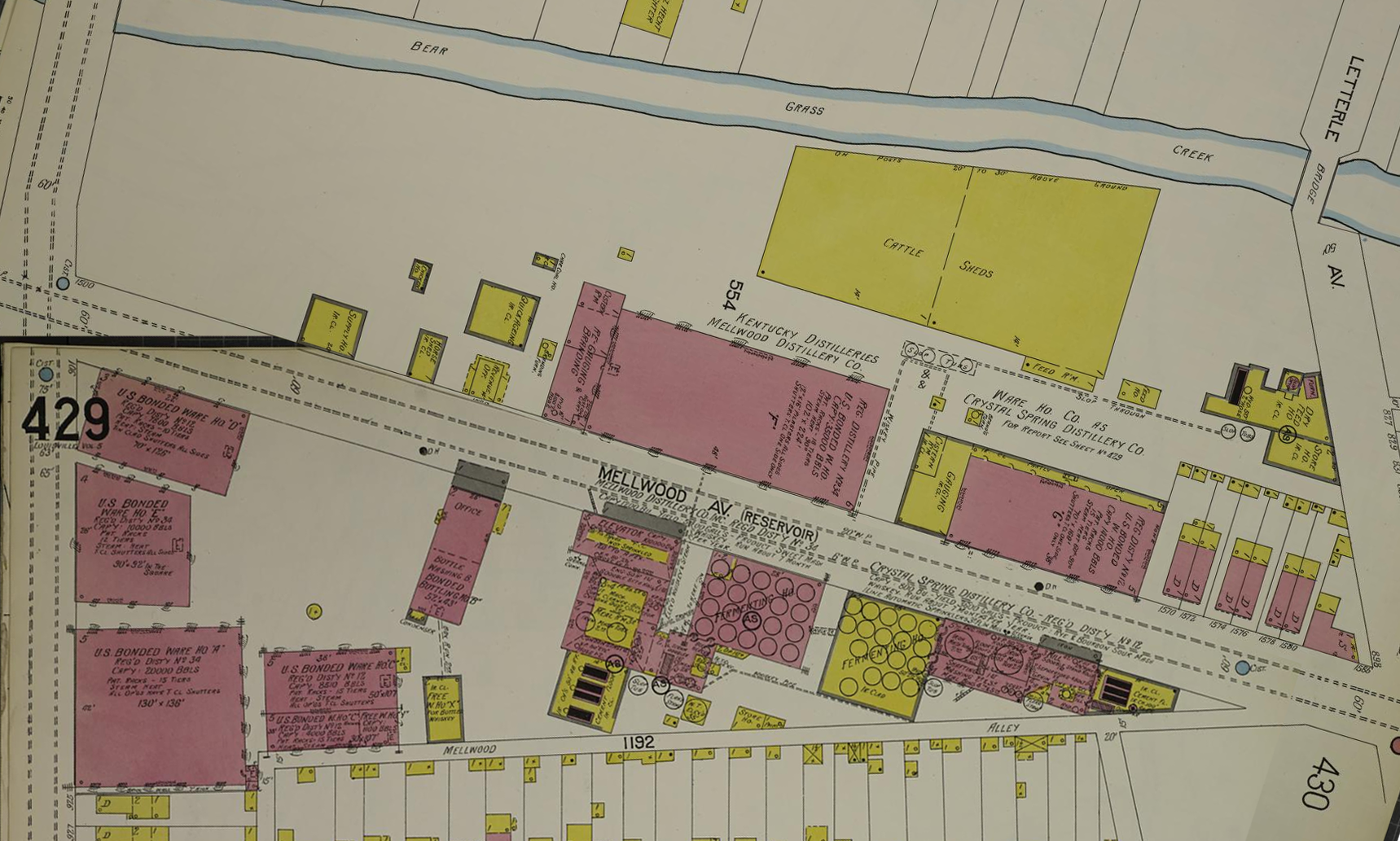

This 1884 atlas of the City of Louisville shows the expansion of the Mellwood Distillery across both sides of then Old Southall St.

The warehouses were steam heated, and an even temperature was maintained in all parts of the building. Further down the road, expansions would lead to a mashing capacity of 1,200 bushels of grain daily and the ability to hold up to 65,000 barrels of aging whiskey, later expanded to 70,000 barrels.

The warehouses were steam heated, and an even temperature was maintained in all parts of the building. Further down the road, expansions would lead to a mashing capacity of 1,200 bushels of grain daily and the ability to hold up to 65,000 barrels of aging whiskey, later expanded to 70,000 barrels.

Insurance underwriter records suggest that in 1892, the distillery was built of brick and equipped with a metal or slate roof. The property included seven warehouses, all brick with metal or slate roofs. The property also included a fermenting house, a grain elevator, and a cattle barn standing 220 ft NW of the still house.

The company opened a branch office in Chicago in 1892, likely a sales office. It was located at Suite 1119 of the Monadock Building, subsequently moved to a suite at 135 Dearborn Avenue. This office disappeared from Chicago directories after 1896.

In 1895, the original Mellwood Distillery building was replaced by a six story building constructed of brick, stone and steel, according to insurance records.

Swearingen’s distillery produced a wide array of brands, with Mellwood Whiskey serving as the flagship. Other notable labels included “Dundee Club,” “G. W. S. Old Watermill,” “Marble Brook,” “Montpelier Rye,” “Normandy Club,” “Normandy Pure Rye,” “Rubicon,” “Runnymede Club Bourbon,” “Runnymede Club Pure Rye,” and “Runnymede Club Whiskey”. These brands gained national recognition, establishing Mellwood as a respected name in the whiskey trade. Swearingen actively marketed his products through advertising and giveaway items like etched bar bottles and shot glasses.

It is important to note the connection between Mellwood Distillery and another prominent name in bourbon history: Brown-Forman. George Garvin Brown and his half-brother, John Thompson Street Brown, Jr., founded Brown-Forman Co. in 1870. Initially operating as J. T. S. Brown & Bro., the firm did not distill its own whiskey but purchased quality straight whiskies from various distilleries, including the Mellwood distillery. They then blended and sold these whiskies under brands like “Sidroc Bourbon” and “Mellwood Bourbon”. This indicates that Brown-Forman was a significant customer of Mellwood Distillery in its early years, sourcing whiskey from them to create their blended products. Later, Brown-Forman introduced the “Old Forester” brand, which was bottled to prevent adulteration. Chuck Cowdery notes that pre-Prohibition, Brown-Forman, who are still in business today, “bought a lot of its whiskey from Mellwood”.

Beyond Mellwood, Swearingen also had interests in other distilling ventures. He owned the G. W. Swearingen Distillery in Deatsville in the late 1860s and early 1870s, which was his first distillery. He was also listed as president of the Spring Water Distillery in Louisville from 1884 to 1887.

In 1889, Mr. Swearingen sold his interest to Rudolph F. Balke and served as Vice President. Following the sale to the Whiskey Trust, both Swearingen’s and Balke’s names disappeared from Mellwood’s listings, as the Trust inserted its own management team.

His entrepreneurial spirit extended beyond distilling. He became president of the Kentucky Title Company. In 1890, he organized the Union National Bank in Louisville, which quickly became one of the city’s strongest and most popular banks. He also served as president of the Kentucky Public Elevator Company.

In his later years, Swearingen was prominently connected to the Presbyterian Church and served for years as president of the board of trustees of the Presbyterian Orphanage of Louisville, contributing generously to its support. He was also among those who met in 1880 to form the Kentucky Distillers Association. In 1898, Swearingen suffered a stroke, leading to temporary paralysis. He continued to experience health issues, and after suffering a third stroke in August 1901 and being paralyzed for several weeks, George W. Swearingen died on December 18, 1901, at his home in Louisville. His funeral was a significant event, attended by many prominent Louisville figures, and he was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery. His obituary in the Louisville Courier-Journal highlighted his sound judgment, broad intellect, and high character.

LEADERSHIP CHANGES AND THE WHISKEY TRUST

Mellwood also played a crucial part in the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, spearheaded by Secretary of the Treasury John G. Carlisle. As the bill neared its final hurdles, Colonel T.H. Sherley of the Sherley Distillery in Oldham County, R.F. Balke of the Mellwood Distillery Company, and G.H. Cochran, President of the Kentucky Distillers’ Association went to Washington to make sure no amendments were added that might sideline the bill, which had already spent nearly a year bouncing through the halls of congress.

In the end, the wholesalers lost and the reputation of American whisky won. The bill was passed by the House and Senate and was signed into law as the Bottled-in-Bond Act by President Grover Cleveland on his last day in office, March 3, 1897.

The late 1890s witnessed the growing influence of the “Whiskey Trust,” formally known as the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company also known as Julius Kessler & Co., a consolidation of numerous distilleries with the aim of controlling the industry. This trust was formed through a series of acquisitions, often under pressure, and by 1899, Mellwood Distillery was among the distilleries acquired by the Trust for $1,240,790.

The sale to the Whiskey Trust was not without its complications. In September 1900, R. F. Balke, representing the Mellwood Distilling Company, filed suit against the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, alleging a default in payment of the purchase price. Balke claimed that a balance of $266,790 was still owed on the agreed price of $1,201,790. He sought a judgment for the unpaid amount, a receiver for the property, and an injunction to prevent the Trust from disposing of or encumbering the distillery.

Under the ownership of the Whiskey Trust, Mellwood Distillery continued to operate, contributing to the Trust’s vast holdings and strategies in the bourbon market. The Trust aimed to consolidate production in larger plants and control pricing within the industry. Mellwood’s brands were likely integrated into the Trust’s portfolio, and the distillery served as a production and possibly a bottling site.

This 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map shows the size of Mellwood Distillery.

THE TURN OF PROHIBITION

The advent of Prohibition (1920-1933) marked a dramatic turning point for the Whiskey Trust and the entire American liquor industry. With the enforcement of the Prohibition Act in 1920, the legal production of whiskey ceased nationwide, forcing the closure of distilleries controlled by the Trust, including the Mellwood Distillery in 1918. This seemingly brought an abrupt end to the Trust’s core business of distilling and selling alcoholic beverages.

In 1921, The Trust demolished neighboring Crystal Springs but spared Mellwood, although the distillery room, fermentation room and bottling room were completely gutted. (Left) A view of Mellwood Ave. from Frankfort Ave. to Brownsboro Rd in 1921. The bridge crossing the street was used to roll barrels between buildings. (Right) An exterior view of the abandoned Mellwood Distillery. Concrete slabs are on the ground in front of abandoned buildings with broken windows from 1929.

However, the Whiskey Trust demonstrated remarkable adaptability by leveraging the medicinal whiskey exception within the Prohibition laws. This loophole allowed licensed physicians to prescribe whiskey for therapeutic purposes, creating a continued, albeit restricted, market for existing aged stocks. The American Medicinal Spirits Company (AMS Co.) emerged as a vital entity during this period, heavily backed by the Whiskey Trust. AMS Co. managed the vast inventory of whiskey held in warehouses and bottled it specifically for medicinal sales. Notably, brands such as Old McBrayer, distilled at Mellwood Distillery in 1917, were bottled by AMS Co. under these medicinal permits.

Recognizing the enduring value of their considerable aged whiskey reserves, the Whiskey Trust strategically focused on warehouse consolidation. The Liquor Concentration Act of 1922 mandated the centralization of all distilled spirits in government-bonded warehouses, a move that inadvertently benefited large holders like the Trust. This ensured the safekeeping and control of their valuable inventory during the dry years, positioning them for the eventual return of legal sales.

Beyond the medicinal market, the entities that comprised the Whiskey Trust also pursued diversification into other industries. The Distillers Securities Company, an earlier iteration of the Trust, had already established the Industrial Alcohol Company in 1906, a strategic move that proved advantageous during World War I due to the increased demand for industrial alcohol. As Prohibition took hold, the Distillers Securities Company further adapted by rebranding as the U.S. Food Products Company. This new venture engaged in the production and sale of non-alcoholic goods such as yeast, vinegar, and cereal products, demonstrating an attempt to navigate the restrictions on alcohol by exploring alternative markets.

A pivotal moment in the Whiskey Trust’s survival strategy during Prohibition was the formation of National Distillers in 1924. This was the result of a merger between the U.S. Food Products Company and the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, the latter being the direct successor to the core of the old Whiskey Trust and the owner of properties like Mellwood. The creation of National Distillers was a strategic rebranding, shedding the controversial “Trust” name and preparing the organization for the anticipated repeal of Prohibition.

By the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, National Distillers emerged as the largest holder of aged whiskey stocks in Kentucky. This strategic preservation of their inventory during the dry years provided them with a significant competitive advantage as the legal sale of alcohol resumed.

POST-PROHIBITION WELCOMES GENERAL DISTILLERS

The end of the long dry spell of Prohibition in 1933 heralded a new era for the American whiskey industry, and in Louisville, Kentucky, the grounds of the old Mellwood Distillery were poised for a resurgence. Walter L. Borgerding emerged as a key figure in this revival.

Born on a November day in 1894 in Kentucky, his early life took a poignant turn when his German immigrant parents passed away, leaving him and his sister in the care of Reverend Henry Frigge, a childless minister of the Evangelical Church. His formative years were spent in local public schools, culminating in his graduation from du Pont Manual Training High School.

Venturing into the world of commerce, Borgerding found his niche in banking. He began his career at the German National Insurance Bank, an institution that would later evolve into the Liberty Bank and Trust Company, situated at the bustling intersection of Second and Market Streets. His dedication and acumen were evident as he spent thirteen years at Liberty Bank, steadily climbing the ranks through various promotions until he achieved the esteemed position of vice-president. During his time there, the bank flourished, solidifying its status as a significant financial pillar in Louisville.

However, Borgerding’s burgeoning banking career was temporarily paused by the call to duty. He served as a dedicated officer in the 36th Division during the tumultuous years of World War I in France, an experience that undoubtedly shaped his perspective and leadership skills. Upon his return, he resumed his promising career in finance.

A significant personal milestone occurred on December 29, 1917, when Walter married Rozália Hertelendy in Jefferson, Kentucky. Their union was blessed with at least two children, Vivian, born in 1919, and Walter Leroy, born in 1920. Notably, his wife’s family, the Hertelendys, were involved in the cooperage business, a connection to the world of barrels that may have subtly sowed the seeds for his future foray into the distilling industry.

The year 1933 marked a pivotal point in Walter L. Borgerding’s life. With the impending repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, the landscape of the American spirits industry was on the cusp of dramatic change. Sensing this shift and perhaps drawing upon that latent connection to the cooperage trade, Borgerding made a bold decision: he resigned from his prominent role as vice-president of Liberty Bank and Trust Company. This move signaled his decisive transition from the world of finance towards the uncertain yet promising terrain of the distilling business, ultimately leading to the establishment of the General Distillers Corporation of Kentucky.

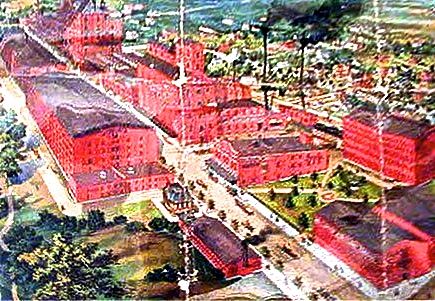

This new entity set its sights on the Mellwood Avenue property, which had previously housed the Mellwood and Crystal Springs plants under the ownership of the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Corporation, a successor to the infamous Whiskey Trust.

The years following Prohibition saw extensive activity at the Mellwood Avenue location as General Distillers embarked on a comprehensive renovation project. The existing buildings were remodeled, and all-new machinery and equipment were installed to bring the distillery back to modern operating standards. This significant investment also included the construction of new bottling plants and warehouses, substantially increasing the overall value and capacity of the property. Records are inconsistent and the plant was assigned DSP-KY-34, yet there is a label called “Number 30” with a picture of the distillery which would lead one to believe it was supplied DSP-KY-30.

By December 13, 1935, General Distillers was ready to begin production, marking a significant milestone in the revival of the Mellwood site. Their initial setup included a single pot still, a few wooden fermentation tubs, and a couple of cookers, signaling a commitment to traditional whiskey-making techniques alongside modernization. While embracing progress, General Distillers also proudly touted its adherence to “old-world bourbon-making techniques” and its connection to the legacy of pre-Prohibition distillers.

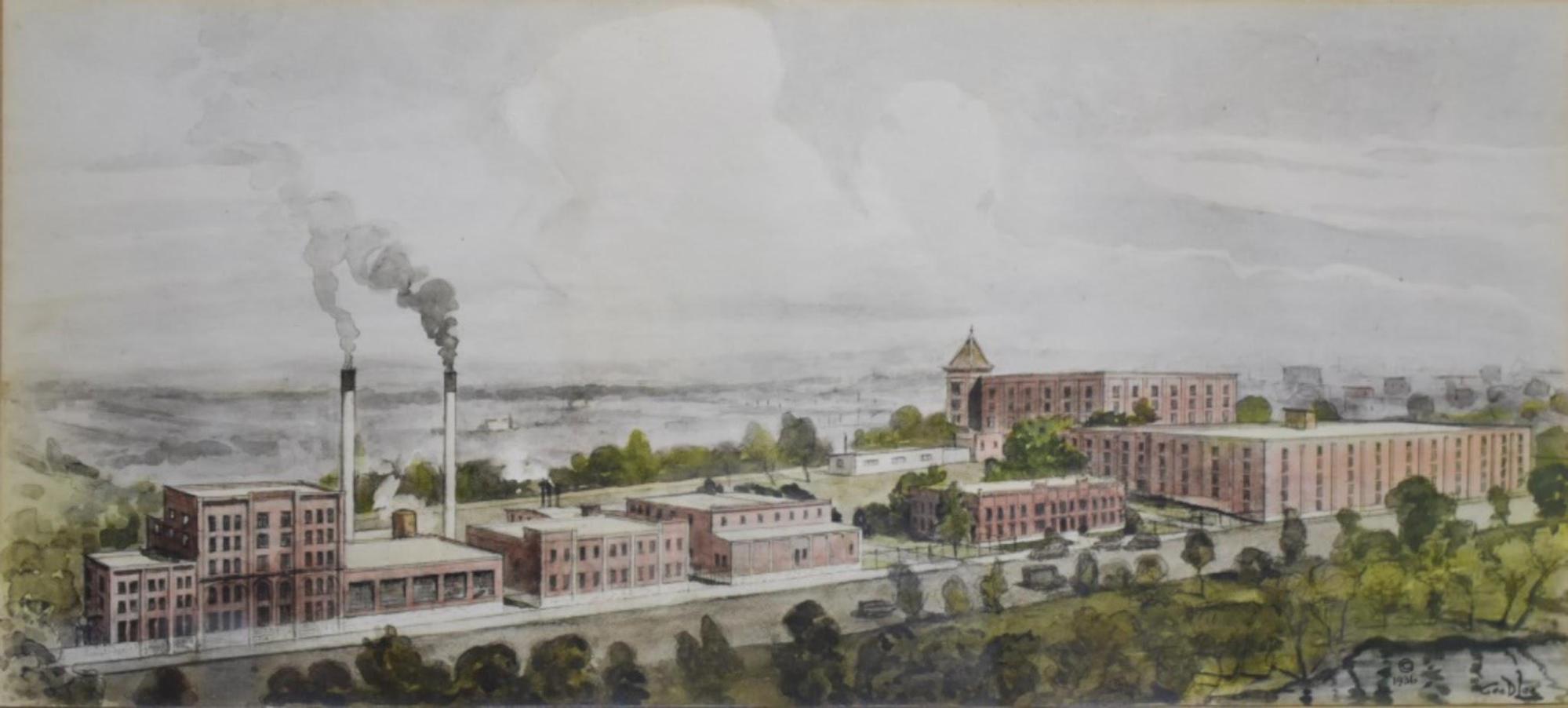

The pictures below show the main building prior and after renovations. Going from a Richardsonian Romanesque lines, peaks, and ornamentations to less ornate sensibilities of mid-1930’s Modernism.

As far as we know, General Distillers did not continue creating the Mellwood label because it was under ownership of National Distillers at that time. However, the company also established its own portfolio of brands, with Old Kentucky General, Derby Town, and Kentucky Nectar becoming some of their most recognizable offerings. Additionally, General Distillers engaged in bulk whiskey sales and provided bottling services for other companies, including the esteemed Stitzel-Weller Distillery. In 1936, the landscape of the General Distillers Corporation was captured in a watercolor by artist George D. Lee, and photographs taken within the corporation in 1940 offer further glimpses into its operations.

By 1945, General Distillers had grown to employ 105 people and boasted a production capacity of 500 bushels of grain per day when actively distilling whiskey. During the Korean War, the distillery played a crucial role in national defense, devoting its entire facilities to the production of industrial alcohol for the U.S. Government, increasing its production rate threefold to 1,500 bushels of grain per day.

Despite navigating the complexities of the post-Prohibition era and surviving various industry shifts for a period, General Distillers eventually faced the challenges of a changing bourbon market. While neither of his children, Vivian and Leroy, were interested in the business, General Distillers ultimately ceased operations. Distilling ended in the 1960s, while bottling continued for a bit more before all but one building was demolished by 1974. Walter L. Borgerding passed away not long after, in 1977. Though the distilling legacy on Mellwood Avenue under the General Distillers name came to an end, the story of Walter L. Borgerding’s efforts to revive the historic site stands as a testament to the resilience and entrepreneurial spirit of the Kentucky bourbon industry in the wake of Prohibition.

PURSUIT ON MELLWOOD

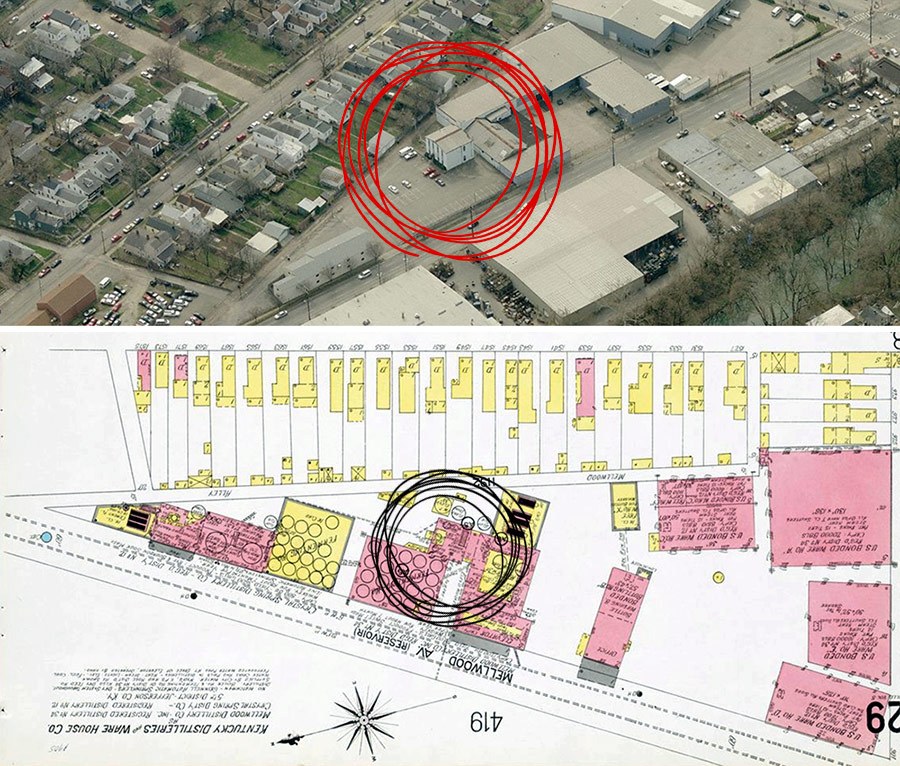

The industrial landscape along Mellwood Avenue in Louisville, Kentucky, bears little resemblance to its former self. Once the site of the bustling Mellwood Distillery and General Distillers Corporation of Kentucky, the entire complex underwent a significant transformation in the 1970s. The original distillery buildings were razed and replaced with structures designed for modern industrial use, primarily warehousing and logistics. A possible exception is an office building on the north side, which may be a surviving remnant of the original Mellwood Distillery.

Fast forward to February 28th, 2023, a significant milestone for Kenny Coleman and Ryan Cecil, the founders of Pursuit Spirits. Five years after launching their venture in 2018, they signed a lease for the building at 1700 Mellwood Avenue. This 16,000-square-foot facility, divided into two 8,000-square-foot bays and complemented by office spaces, would become the new home for their burgeoning whiskey business.

The journey to operational status was not without its hurdles. Securing the necessary permits and approvals proved to be a lengthy process, consuming nearly seven months. Finally, they received their Distilled Spirits Plant number from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) on June 30th, 2023: DSP-KY-20135. Initially, they had hoped to obtain DSP-KY-34 as a symbolic nod to the site’s distilling legacy. However, the government cautioned them about potential delays and the uncertainty of approval, leading them to opt for a more expedient route.

It wouldn’t be until September 2023 when Kentucky and Louisville licenses would be approved so the building could be completely operational.

The rich history of the Mellwood Distillery remained largely unknown to Kenny and Ryan until a serendipitous visit during the permitting phase. Jason Brauner of Bourbon’s Bistro and Buzzard’s Roost, upon visiting the site, shared tales of the distillery’s storied past, sparking Kenny and Ryan’s curiosity. This encounter ignited a deep dive into the archives, revealing a forgotten chapter of Kentucky’s distilling heritage.

Their exploration took on a new dimension when, after discussing their findings on their podcast, “Behind The Pursuit,” listener Chris Hanes generously gifted them a collection of artifacts acquired from auctions. These items, remnants of the original Mellwood Distillery, fueled their passion further. Kenny delved into the history, sharing a comprehensive lesson on Episode 66 of “Behind The Pursuit.”

This renewed interest in the distillery’s legacy inspired a creative endeavor beyond their core Pursuit United portfolio. Kenny and Ryan embarked on a project to revive vintage Mellwood labels. They began acquiring unique lots of whiskey and bottling them in 375ml hip flasks, complete with faux tax strips, replicating the aesthetics of the past. While these flasks are modern interpretations, they symbolize a new chapter for the iconic Mellwood labels, a testament to the enduring spirit of Kentucky’s distilling heritage.

Thank you to the following sources of information on being able to piece together this timeline of Mellwood and General Distillers:

- The Chuck Cowdery Blog: Old Anvil Bourbon and Louisville’s Mellwood Distillery

- Those Pre-Pro Whiskey Men!: George W. Swearingen Was the “Mellwood” Man

- University of Louisville Public Images

- Sipp’n Corn®: Mellwood Bourbon – The Early Fight Against Phantom Distilleries

- The Mellwood Dist. Co. Distillery, RD#34, 5 th District, Jefferson County, KY (1901)

- Bourbon in Kentucky: A History of Distilleries in Kentucky by Chet Zoeller

- Bluegrass Bourbon Barons

- Atlas of the City of Louisville, Ky. and Environs, 1884

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Louisville, Jefferson County, Kentucky. | Library of Congress

- Worthpoint.com

- Whisky Auctioneer

- Pacific wine and spirit review : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- Louisville J. Co. M. S. v. General Distillers, 257 S.W.2d 543

- Bullitt County History – George W. Swearingen Obituary

- The Origins of Bottled-in-Bond (2024 Updated Facts) – Whiskey Lore